The white linoleum floors, once reverberating the sounds of scuffling shoes and adolescent conversations, now echo the steady hum of computers and printers of administrative offices. An old trophy case showcases the achievements of students who long ago walked these halls, but have since graduated.

Lincoln Center, off of Merritt Mill Road, has lived many lives. Once Lincoln High School, the building served as a school for African-American students from 1951 to 1966.

Although African-American students only walked its halls for 15 years, the school instilled pride in the African-American community whose children, prior to the building of Lincoln High School, had been attending the old Lincoln High School on Church Street, where the Northside School now stands.

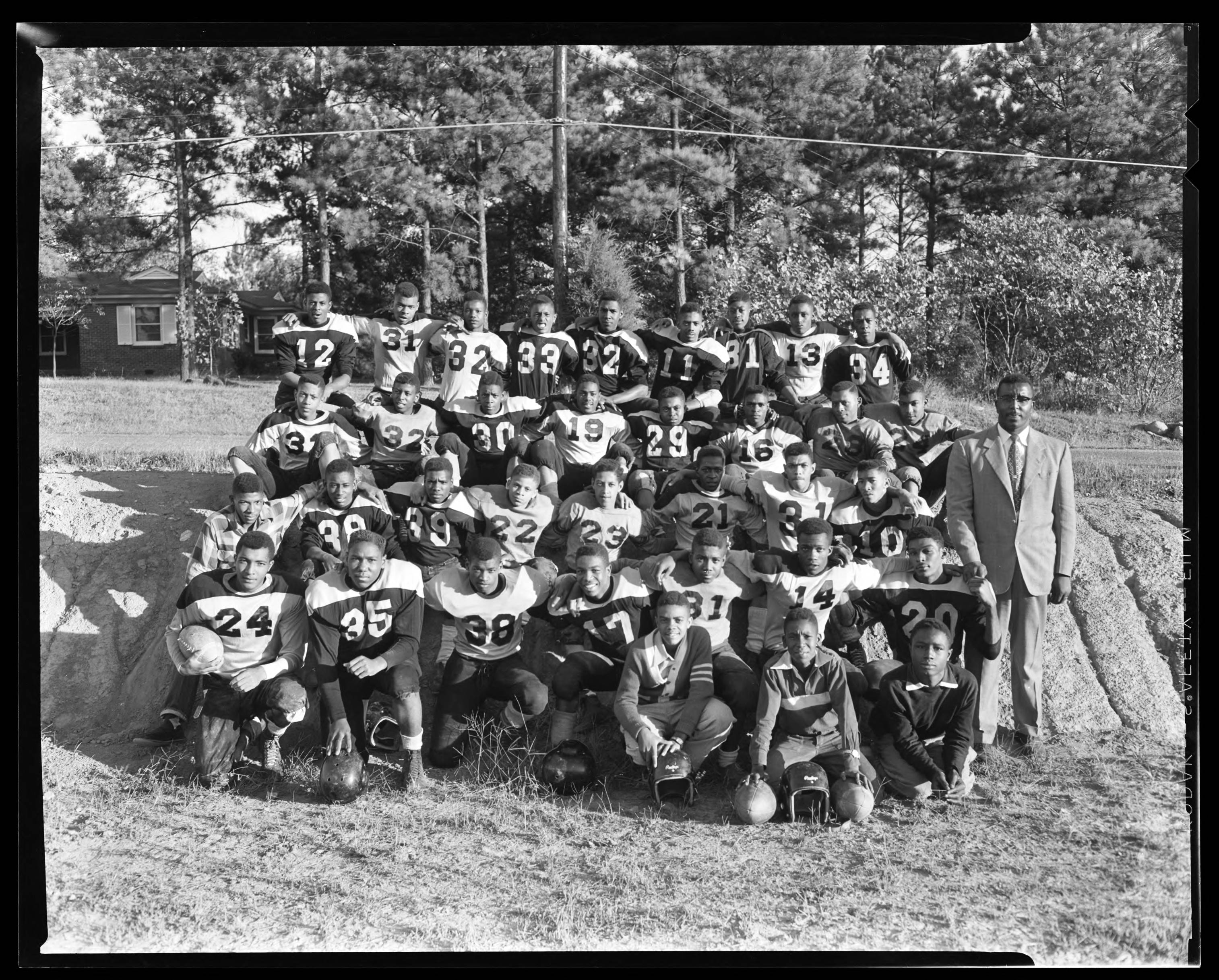

“At this particular school here, we had a fantastic education despite the limitations that we had,” said David Mason, Jr., president of the Lincoln-Northside Alumni Association. “We were well known for academia, sports, music. We won all kinds of state awards. In football, we probably had the only undefeated, unscored-upon team.”

“Oh goodness, our band was something to behold,” Mason added, after a long pause.

Prior to being Lincoln High School and then Lincoln Center, the building that stands on Merritt Mill Road was the Orange County Training School. This school began operating in 1916 but burned down only a few years later.

During the school’s time on Church Street, the school was renamed, becoming Lincoln High School, after the parents of its students argued that ‘Orange County Training School’ was not reflective of the amount of academic rigor they wanted their children to undergo.

Lincoln High School moved back to its original location on Merritt Mill Road after a new building was built in 1951.

In 1960, the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City School District began the process of integrating, rendering the purpose of Lincoln High School obsolete. African-American and white students both moved to the newly built Chapel Hill High School.

“The schools were no longer going to be segregated, so we were going to get all these tremendous facilities that other kids had been getting,” Mason said. “But needless to say, it never did come to fruition, and in 1966, this facility closed and that was the end of Lincoln.”

For Mason, the two schools didn’t even compare.

“You had so many students to complain about not being called on by their teachers. The athletic program at Chapel Hill High was nothing like it (was) here.”

The Lincoln High-Northside Alumni Association will soon commemorate these 50 years of “so-called desegregation,” Mason said.

The Lincoln Center now houses administrative offices for the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City School District.

Art teachers across the district chose pieces of art created by their students to display at the Lincoln Center. Summer camps are sometimes held in its classrooms, and a menagerie of sports teams use the expansive fields at the building’s front to practice. More changes to the Center are on the way. A bond referendum this November will decide if the building will expand.

“If the project is funded and continued as planned, the Lincoln Center campus will be a unique learning environment that includes both a universal pre-K center as well as a state-of-the-art alternative high school,” said Jeff Nash, executive director of public relations for Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools.

There will always be remnants of the Lincoln Center’s past. Right outside the main entrance to Lincoln Center, by the flagpole, is a memorial to the students who studied at and graduated from Lincoln High School and the Orange County Training School. It stands as a permanent reminder to a time when African-American and white students were not permitted to study and learn in the same spaces.

Sarah Chaney contributed reporting.